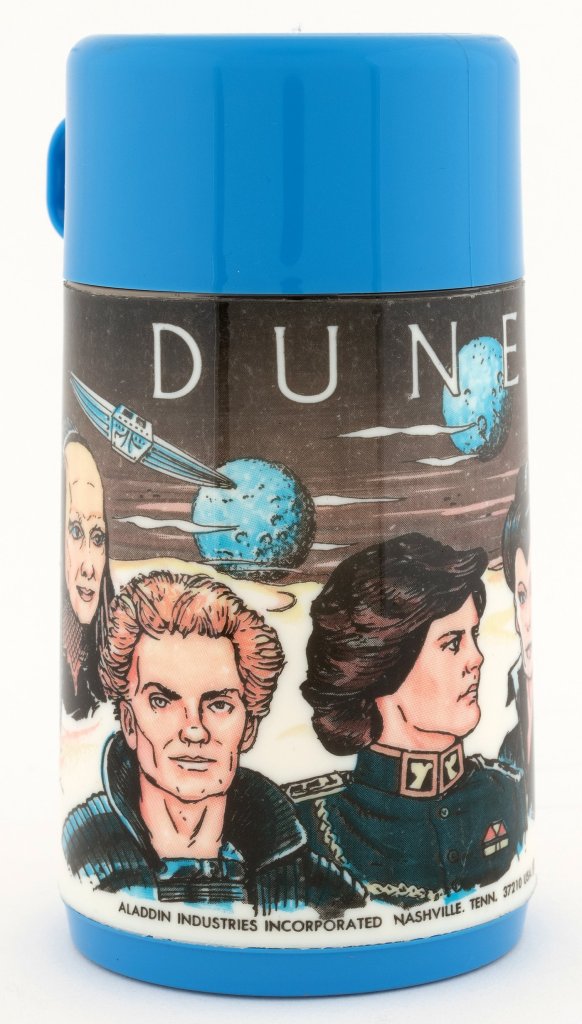

My introduction to David Lynch’s Dune was through a friend’s Dune-themed lunchbox in elementary school. It was 1984, I was six years old, and in the first grade. My main exposure to science fiction at that time was via the Star Wars films and Star Trek. I knew nothing about Frank Herbert’s classic novel, much less Lynch’s film.

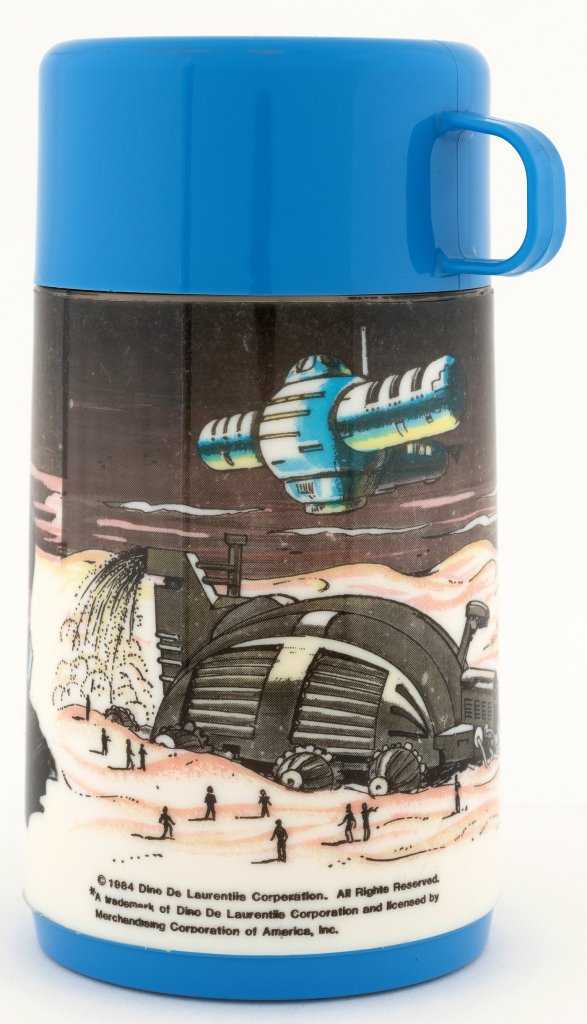

But that lunchbox looked so damn cool, with knife-wielding characters in futuristic armor. The thermos showed more characters, as well as a spaceship and a hulking, wheeled surface vehicle.

At the time, I had no idea what I was looking at, but I knew I wanted to find out.

Skip forward a few years to 1987, when my parents bought a VHS player. When we visited video rental stores, I was always drawn to the science fiction and fantasy section. And of course, I talked my parents into renting Dune. I still remember watching it that first time, with Princess Irulan appearing from a starry backdrop and speaking of spice, Fremen, and a messiah. I was still in the dark regarding Herbert’s universe, but from that moment, I was hooked.

Watching Lynch’s Dune at that early age imprinted the film onto my consciousness. It was unlike anything I had seen before, and esoteric in comparison to other SF movies. I loved the stillsuits, the worms, the otherworldly portrayal of Paul’s prescience, and even at that pre-pubescent age, I had a crush on Lady Jessica, played by Francesca Annis.

I remember how negative Starlog Magazine was, regarding the film, and in my teens, I’d hear less than stellar opinions of it from fellow SF fans. I’ve never understood these rejections from fandom. Lynch’s film has flaws, but it remains one of the best scifi movies of the 1980s, a respectable adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel, and a unique piece of cinema in its own right. Now, upon its 40th anniversary, I’ll look at how this film holds up in relation to Herbert’s novel, its legacy, and its impact on me.

This essay assumes the reader has watched the film, so I will not go into every detail regarding scenes, characters, etc.

Fidelity to the Source Material

Lynch’s film encapsulates most of the novel’s events rather well, albeit in a shortened form. The movie’s running time is only 137 minutes, so some choices were understandable. Herbert’s book is complex, with considerable worldbuilding, and distilling that into a 2-hour Hollywood movie is nearly impossible (even Denis Villeneuve didn’t manage to capture everything despite having two films, and I regard his Dune 1 & 2 as masterpieces).

We’re treated to a short monologue by Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen’s floating head is still talked about to this day in the fan community), and this is a good choice. It quickly lays out what the spice is, its importance, and the only place in the universe where it can be found: the planet Arrakis, also known as Dune. Given the novel’s complexity, I applaud Lynch for this approach. The sad part is, this is the most we see of Irulan in the film, and she barely has any lines afterward.

The movie starts with the Spacing Guild paying Shaddam IV a visit, and their plot to destroy House Atreides and assassinate Paul sets up the story. Right away you see the brilliance of the set and costume design. It doesn’t look like typical science fiction (especially for the 1980s), but it isn’t high fantasy, either. The emperor’s throne room is colorful and gilded with gold. Shaddam’s generals are dressed in uniforms that resemble those worn by World War I European officers, while the Guild wears black, vinyl suits and have shaved heads. The Guild navigator, in the tank of spice gas, feels truly alien, and the use of a future language underlines the idea that we are seeing humans twenty millennia into the future. It’s an effective opening, but it might seem obtuse to those unfamiliar with the book. Yet if one pays attention, it’s not hard to follow.

The use of interior monologue voice over was different from most films in the genre (despite Blade Runner using it two years prior), but I like it. This way, we hear the actors speak the character’s thoughts from the novel. Not only that, since Dune is all about mental will, political intrigue, and heightened human consciousness, it grants an intimacy with the characters that would be difficult to achieve otherwise.

The film next shows us the protagonist, Paul Atreides, as he prepares to leave for Arrakis. Kyle MacLachlan is a good match for our hero, and he portrays Paul’s early innocence and then later resolve equally well. Lynch handles the small character beats, like Yueh’s, very well, too. We’re given scant information about these people in a short time, but we understand who they are immediately, even if one hasn’t read the novel. Grizzled Gurney, fastidious Thufir, distant Yueh—they’re emblematic of the excellent character work done by the film’s actors. They’re borderline archetypes, which is common across storytelling in general, but particularly useful for a far future mythos such as Dune. Much like their counterparts in Herbert’s book, they anchor the audience with the familiar in a world that, for most filmgoers, must have seemed bizarre.

Soon we’re treated to the Gom Jabbar scene, where Reverend Mother Mohiam tests Paul to see if he might be the Kwisatz Haderach, an individual her organization has been trying to breed for centuries. It is still effective, and Siân Phillips, portraying Mohiam, delivers an exceptional performance. Paul passes the test, which infers he might be the superbeing—but we also learn that his father, Leto, will not survive once the family relocates to Arrakis. This is important, because seeing the future is one of the foundations of the Dune setting, and creating that seemingly inevitability adds a layer of anxious providence to the film.

Next we’re shown Giedi Prime, homeworld of the film’s main antagonists, the Harkonnens. It’s an industrial planet of sickly green cubicles, oil-filled gutters, and augmented abominations that might have been human once. Lynch’s penchant for the grotesque is well-used on the Harkonnens; they are laced with sweat, crude, cruel, and lack any empathy whatsoever. When Rabban crushes a tiny creature in a bottle simply to provide one sip of its fluids, and then discards the bottle into a gutter, we see all we need to know about these people—at least, for the film. It’s a bit over the top, however, and makes the Harkonnens a caricature, since we learn nothing else about them. In particular, the homophobic portrayal of the main villain, Baron Harkonnen, hurts the film, especially in light of the AIDs crisis during the 1980s. This has aged even less well in the 21st century. The Harkonnens aren’t quite this vulgar in the novel, and Lynch’s take on them undermines their status as a scheming, dangerous foe. It’s hard to take them seriously after this sequence.

The Guild Heighliner scene, where the Atreides family travels from Caladan to Arrakis, is still majestic. It’s one of my favorite moments in the movie, due to its sense of scale and the incredible ability to ‘foldspace’: traveling instantaneously to another part of the universe. Folding space in this adaptation is a transcendent experience more about sensations than numbers, which is at odds with space travel’s depiction in nearly all other science fiction narratives, even now. And I love the Atreides pug. Not only because I’m a dog owner myself, but it’s another way of showing that Paul and his family respect life and possess the empathy to love a pet, contrasting the Harkonnen’s selfish brutality.

At this juncture we hear Eno’s ‘Prophecy Theme’ for the first time in the film. It remains supremely evocative and captures the setting’s otherworldly ambiance. Watching this now, I wonder if Lynch’s movie started my obsession with the desert and its rendering in fiction.

Finally, the Atreides family reaches Arrakis. Their arrival is presented with medieval pageantry mixed with far future mythology, as if Arrakeen is older than time itself, and we are but transient visitors. Soldiers marching with banners held high, Lady Jessica in her lovely gown (and that iconic coiffure); Leto and Paul in their military uniforms—image is everything, especially for the powerful. Yet we see the shimmering of the planet’s oppressive heat in the desert air; a hint that this world will burn away who these people thought they were. It also implies they only think they control Arrakis, while in truth, it is the forge in which they’ll either disintegrate, or be honed into someone stronger.

As Paul and Leto fly out to watch spice mining, we get our first glimpse of the Fremen, as well as Lynch’s problematic portrayal of them: they are nearly always white, male, and do not look like people who have ever dwelled in a desert. More on that later. The best part of this scene is the description of a stillsuit, and Bob Ringwood’s design remains one of the best costumes in scifi history. From this point forward, with few exceptions, it is also the only thing Paul will wear for the rest of the film. My main issue with that is the stillsuit then becomes the equivalent of a superhero costume, like Superman and his cape. Fremen don’t wear anything else?

The spice harvesting scene is great, showing the anxiety and magnitude of nabbing the precious substance before a sandworm appears and tries to sallow the machinery. It’s very true to the book, too. Leto’s comment of ‘Damn the spice!’ is a great character moment, both in the novel and in the movie. It illustrates, in one sentence, that Leto cares more about people than wealth.

Up to this point Lynch had been largely faithful to Herbert’s book, but that fidelity decreases somewhat as the film progresses. That’s understandable to a point, but some of Lynch’s choices were odd, as I’ll numerate.

Soon we are treated to the fall of Arrakeen, after Yueh betrays the Atreides family and the Emperor’s forces eradicate the hapless defenders. But I have complaints about this entire sequence. The Sardaukar suits are the single weak design in Ringwood’s otherwise wonderful bevy of costumes. They look like trash bags combined with welding helmets. The Harkonnen soldier armor is far better looking, as well as more functional. Can you run around in the desert while wearing a clumsy vinyl bag, wearing a helmet with a limited field of vision, and still call yourself one of the most dangerous troopers in the universe? Ha, nope. The action scenes here are of poor quality, even for their time; the Atreides soldiers put up a pathetic resistance. I understand this is to illustrate the element of surprise as well as Sardaukar fighting superiority, but come on. House Atreides was supposed to be a threat to the Emperor, not lasgun fodder. The one good moment is Gurney charging the enemy while holding the family pug. I’m more afraid of that dog than I am of any Atreides soldier in this film. However, the overall narrative here is true to the novel, even down to Kynes getting tossed to the desert, where he will die.

Afterward, Paul and Jessica escape, and the second half of the film begins. The first half of the film is better than the second, mostly because the latter section feels rushed. The scene where they flee the crashed ship and then encounter a sandworm is a good one (and very faithful to the novel), but then we’re reintroduced to the Fremen.

Once again, we see mostly white males. Their culture is barely shown, and no one in a desert would eschew head scarves, or at least headgear of some kind. It’s like no research went into actual desert dwellers. Paul and Jessica are accepted by the Fremen too easily, but the movie’s running time almost demands it. Chani pops up, but she’s little more than set dressing. We also get our first Fremen uttering ‘It is the legend’ in reference to Paul’s appearance and decisions, but it feels too fast, and, well, it’s corny. His character hasn’t earned that yet, and it’s hard to care that he’s supposed to be a superbeing. At this point the story devolves into a typical Hero’s Journey where the protagonist reclaims his father’s throne. That’s in Herbert’s book, too, but the text accomplishes it with more nuance and depth. Again, the running time is partly to blame, but it’s as if Lynch skimmed over these things to rush us to the Hollywood ending.

Okay, now the Weirding modules: ha. Ha ha. That’s my reaction to them. They are easily my least favorite part of Lynch’s adaptation. The entire concept is silly, but not because they weren’t in Herbert’s book. I understand why Lynch went that route (he didn’t want to show the Weirding Way and its martial art). The sonic weapon doesn’t fit the setting and it’s too powerful. If the Atreides had these, Arrakeen shouldn’t have fallen—even if Yueh had sabotaged them. Come on, there must have been thousands of troops there, and thus thousands of modules for them to use—and not a single Atreides soldier wore one while on guard duty? Yueh magically burned every single one without getting caught? It’s ridiculous. Yueh letting the shield down is believable, but this is too much. And I’m reminded of that as I watch Paul train his Fedaykin with the modules.

Also, at this juncture, Lynch goes for a more mystical presentation of the narrative. ‘Chosen one’ vibes are so strong to the point of stifling the story. The ending is a foregone conclusion.

Having said that, though, the following Water of Life sequence is the heart of the film. It’s dreamlike, meditative. This is where Lynch excels. More of movie should have been like this. It infers an intergalactic consciousness that the worms sense, too, as they gather around Paul’s prone body. His psyche travels to ‘a place that is terrifying to us’, as the Reverend Mother said. That place is the future; traveling without moving. But Lynch doesn’t show why that is special, or why we should care. Paul is able to foresee a great deal by this point in the book, yet in the movie, we get none of that. It’s like he has magical powers, but that is counter to what Dune represents: a long, calculated process to create ultimate power that spirals out of control. In this case, it’s Paul leaving the control of the Bene Gesserit to avenge his father, but meh. The film promised so much more in the first half.

Finally, we get the big, climatic battle where the Emperor himself comes to Arrakis with all of his Sardaukar legions to stop Paul and his Fremen warriors. Again, there’s little drama here; it’s a foregone conclusion, with no challenges to the protagonist whatsoever. And again, the action is less than stellar. (Though I love the shot of Sardaukar firing at a sandworm.) There are no women fighters among the Fremen other than Chani, who never fights save for this finale, and one woman in closeup using a Weirding module. 1984 or not, this was disappointing. It’s a glaring error when viewed in the 21st century, and having read Herbert’s books. Women were just as deadly as men in his series (Honored Matres, anyone?) but Lynch glosses over it.

Alia adds nothing to the film other than staying true to the book: revealing Paul’s identity to the Emperor, and killing the Baron. Ugh, I can’t abide her voice over. But the shot of her holding the crysknife on the battlefield is a classic image, like something from a fever dream.

Now on to the knife fight between Paul and Feyd. It leaves a lot to be desired.

Where did the Fremen get those drums so quickly? The fight choreography is poor, even for the 1980s. Then, after Paul kills Feyd, he uses the Voice on him. Even without a Weirding module, he cracks the floor as well as Feyd’s armor, and turns the man’s eyes white. Er, what? Then the Fremen makes the ‘word of god’ comment? I’m done with the movie by this point—but nope. There’s one more indignity:

The rain scene.

Paul making it rain at the end hurts the film. It adds a metaphysical layer, a spirituality, that doesn’t belong in the Dune universe as a literal force. He’s a highly-trained individual, versed in martial arts, Mentat computing techniques, and Bene Gesserit teachings—but he’s not Gandalf. Why Lynch added this, I will never know. I suppose he thought it felt right, with Arrakis being a desert world, and the Fremen seeking to make it green. The rain could symbolize the change Paul ushers in to the Imperium; but I suspect it’s a cinematic styling, done more for visuals and emotion rather than narrative. Of course, it’s not in Herbert’s novel.

The Film’s Legacy

This version of Dune developed a cult following, but it also tainted the franchise for those who hadn’t read the books. If they disliked the film, they rarely gave the novels a chance, either. Thankfully that perception has changed in the decades since the film’s release. Now it’s usually viewed as an ambitious but flawed classic, and I would have to agree. It got so much right, but so much wrong. A film adaptation doesn’t need to be chained to its source material, but it must present a coherent narrative that at least pays homage to the source’s themes. Lynch succeeded and failed in this—but when he did succeed, he did so brilliantly. So the movie still matters.

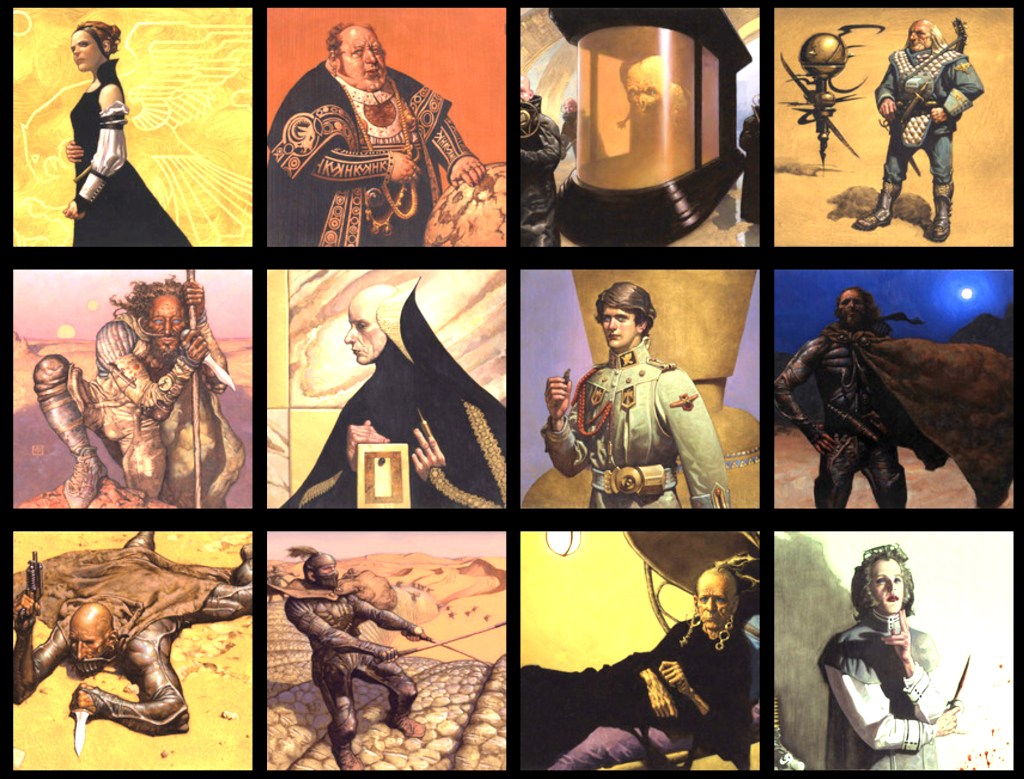

The look of Lynch’s movie influenced the Dune franchise for decades afterward: board games, video games, card games, RPGs, and others. Ringwood’s costumes were the de facto appearance of any Dune character afterward.

The film could use a remaster; artifacts and matte lines detract from otherwise good shots, and the newer 4K restoration isn’t what it should be. Yet there is excellent model and matte painting backdrop work; Gene Siskel was full of shit when he said the film looked ‘cheap’. Its vision sequences are brilliantly psychedelic, and I still prefer this version of the sandworm design over any other (maybe I’m nostalgic).

It’s endlessly quotable for those who grew up with it. ‘They tried and died’ has made many a round in my TTRPG circles, as well as the Juice of Sapho mantra.

There’s other things, too: Lynch burning tires to create the black smoke in the desert battle scenes is emblematic of what we must overcome in the years since the film’s release: human-driven climate change. I wonder if he regrets using those tires. That might seem like a nitpick, but given Herbert’s fascination with ecology and climate, it’s impossible not to consider.

The film highlights how important water is in the real world, which is far more relevant now than it was four decades ago. Bottled, clean water wasn’t even a thing back in the early 1980s, but now it has become a billion-dollar commodity. Access to potable water has been ruled by the Pentagon as one of the 21st century’s key sources for future conflicts. Yet like the Harkonnens, we have the terrible habit of poisoning the very thing that gave us life.

No one made another Dune film for years, until SyFy released a television adaptation in 2000. It’s serviceable, but lacks the panache of Lynch’s version, and delves in metaphysical nonsense that is at odds with the source material. It wouldn’t be until 2019, when Denis Villeneuve made Dune: Part One, when we saw another. Having seen it and Dune: Part Two, I can say that Villeneuve has crafted two of the best SF films ever made, and Dune’s place in our culture is even more secure. But that might not have been possible without David Lynch’s film coming first. As far as Jodorowsky’s failed Dune project, I’m glad it wasn’t made. It sounds fascinating, and I appreciate Jodorowsky’s passion for it, but his narrative choices (Paul dies in his duel with Feyd) and casting decisions (Salvador Dali as Shaddam IV?) would likely have yielded a visually arresting yet lackluster film.

The Cast

Nearly every performance in Dune had weight and is memorable. Lynch’s cast consisted of a very fine selection of actors. I can think of none who were miscast. Yet, I do have thoughts regarding these particular performances:

Kenneth McMillan as the Baron is delightfully wicked, despite my criticism above. He’s an unfettered megalomaniac, with seemingly limitless resources and the power of life and death over billions of people—and that’s just on Giedi Prime. How else do you expect someone like that to behave? So I can forgive some of his hijinks.

Sean Young is underused in the film. We know she can act after her wonderful part in Blade Runner, but in Dune, she’s simply Paul’s lover. She barely has any presence in the film at all, and it feels like she’s there as a connection to the novel, rather than an important character in her own right. A shame.

Leonardo Cimino as the Baron’s doctor is priceless. His doting care of the Baron’s diseased visage is deliciously creepy. ‘Put in the pick, Pete, then turn it ‘round, real neat’ is so Lynchian it’s not even funny, but it’s a great addition.

Dean Stockwell gives one of the best performances of the film as Doctor Yueh. To go from a neutral stance to his rant at the Baron before his death shows great range.

I wished we’d gotten more of Max von Sydow as Liet Kynes; that man could read a laundry list and make it sound dramatic.

The end credits sequence with portraits of the actors is classic but sad, since so many of these people are no longer with us. They’re set against the backdrop of ocean waves on Caladan, which I found to be a nice touch.

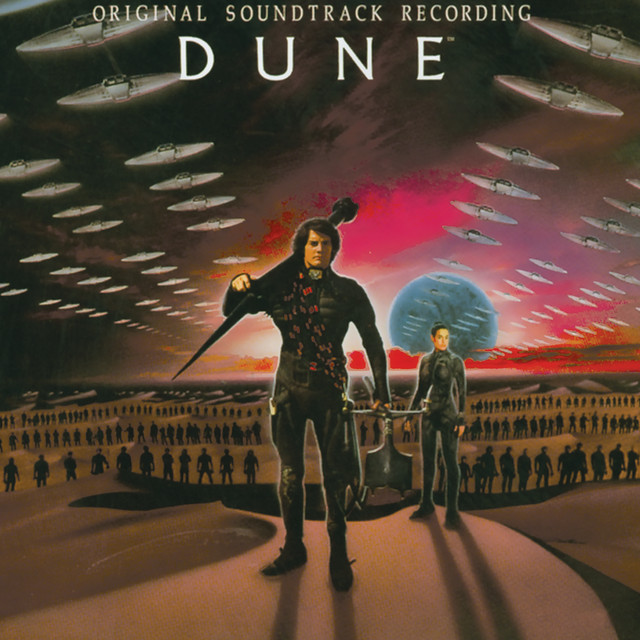

The Score

Okay, I’m on the fence when it comes to Dune’s music. Toto’s score is good but often too melodramatic. I like ‘Title Theme’, but I’m not fond of how ‘Prelude (Take My Hand)’ and ‘Leto’s Theme’ are overused at times. They’re nice pieces, but often clash with the events onscreen. ‘Trip to Arrakis’, played during the Atreides’ family trip from Caladan to Arrakis, is easily Toto’s best contribution to the soundtrack; it lends an ethereal air to the sequence. I loathe their theme for Baron Harkonnen, ‘The Floating Fat Man (The Baron)’; it’s too trite and sounds like something from a children’s Halloween music collection.

Brain Eno, on the other hand, should have scored the whole movie . His ‘Prophecy Theme’ is one of my favorite film themes, ever, and perfectly captures the mood during Paul’s Water of Life sequence. Given how excellent this track is, as well as Eno’s work on his Apollo album prior to this movie, I can only imagine what he might have given us. I daresay he could have produced something equal to Vangelis’s Blade Runner score, but we’ll never know.

Extended Cut

This version of the film is really for Dune purists only—or those who want a constant, narrative voice over that drags on to the point of pulling one’s teeth. I’m a huge Dune fan, but this grows tiresome very fast. You’ll be sick of it even before Paul leaves his bedroom.

The Introduction is great for book fans—detailing the Butlerian Jihad, the rise of the Spacing Guild, etc.—but it would have been terrible theatrically. I can see why it wasn’t used. There’s a few gems in this cut, such as Thufir’s fate (a crime to leave that out of the theatrical version), and Paul’s duel with Jamis. But honestly, the extra material doesn’t improve the overall movie much. David Lynch refused to be associated with it, and as of 2024, Universal has neglected to release it in any format after the DVD went out of print. I still have my copy in the metal case, so there’s that. There’s other cuts of the film, such as a rumored 4-hour version, but…why? I love this movie, but that’s getting ridiculous. There’s a reason these scenes were cut.

Random Observations

The Spacing Guild planet maps showed at the beginning of the film stayed in my mind for years. They’ve influenced my work, such as my first novel, Inherit the Stars, in terms of grounding a story with locations. I wanted to see those worlds; I still do. So now I create my own.

Paul’s filmbook was something I only dreamed I would have in the future. Now I use something much more powerful and versatile: a Samsung tablet.

The Mentat usage of the Juice of Sapho is a great concept for human computers, and Brad Dourif’s recitation of the ‘set my mind in motion’ mantra is a classic.

The Mentat computing that Thufir does on the machine in Arrakeen seems like something from a 1950s scifi movie, but it’s unique due to the setting’s lack of ubiquitous computers. It fits.

The lightning appearing along with the sandworms implies that the creatures—and by extension, Paul Atreides—are forces of nature. I can take or leave it.

The ‘Lovely Feyd’ moment adds little to the film, other than seeing Sting in his Harkonnen underwear. Plus it feels like more homophobia (and incest?), regarding the Baron’s lustful reaction to his half-naked nephew.

Thufir and Yueh prove that emotional conditioning can be broken: Thufir by refusing to harm Paul at the end (see the Extended Cut), and Yueh giving in to the desire to see his wife again at any cost. It shows that no matter how much effort is spent trying to erode human will, it can still topple empires.

The Atreides pug survived! One of the Fremen boys holds the dog in the final scene, where Paul faces the Emperor, the Guild, the Reverend Mother, and Feyd. For the longest time I was unaware of the pug’s fate. Thank you Lynch!

Summation

My love for Dune, and a deeper appreciation for SF, began with this film. Watching it again stirred my emotions as I realized the importance of this movie to me personally. It reminded me of how much this film has influenced my life and my work. If you read my work and come across clones, massive starships, desert worlds, or an awareness of one’s actions in the larger universe and their consequences…those all started with this film. Star Wars opened the door, but Lynch’s Dune gave me a glimpse of what was behind it. It encouraged me to read Herbert’s initial Dune novels in my teens, and then the latter books in my late 20s—and that changed my life in an even greater fashion.

‘The sleeper must awaken’, Leto tells Paul, and this film planted a seed in me that awoke years later in my fiction.

So, despite my criticisms, David Lynch’s Dune still numbers among my favorite science fiction films. I suspect that without it, we not only wouldn’t have the many Dune products we have today—we also would lack another gateway that drew so many into the genre, and into their own imaginations, that Dune 1984 provided.

Leave a comment